By: Robert Shepherd MS, Certified Medical Illustrator, Vice President and Director of Eastern Region Operations,MediVisuals Incorporated

Long before science had advanced to allow imaging of the body in sectional views by computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), medical illustrators were illustrating the body in sectional views because these views are the best way to appreciate some anatomical relationships.

Medical illustrators, physicians, and others who have studied anatomy are familiar with sectional views of the body and appreciate the value of these views in explaining the relationship of anatomical structures. However, accomplished and well respected jury consultants and non-medical illustrator legal graphics experts have expressed concerns that sectional views may be difficult for some jury members to understand. These individuals' opinions are valuable to those of us in the legal graphics business, and I agree with their opinions that, when other views can communicate a particular relationship message equally as well or better, sectional views should be avoided. I also believe most of these experts will agree that there are times and places in which sectional views of anatomy are the best way to appreciate some anatomical relationships. Granted, there have been times when we have been working on specific cases and experts have insisted that sectional views be absolutely and unconditionally avoided. Unfortunately, in these situations the experts were unable to suggest a more effective view to communicate the relevant anatomical relationships (at least in a way that was practical in terms of time and expense). That being the case, sometimes the sectional views were used despite the input of the experts, and at other times, the relationships of the structures had to be explained without the benefits of graphics.

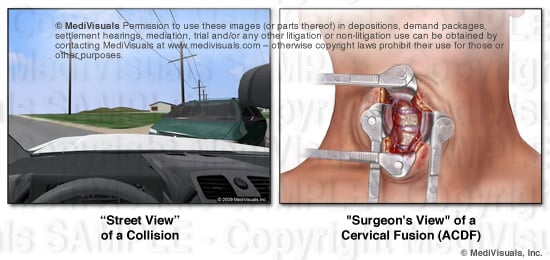

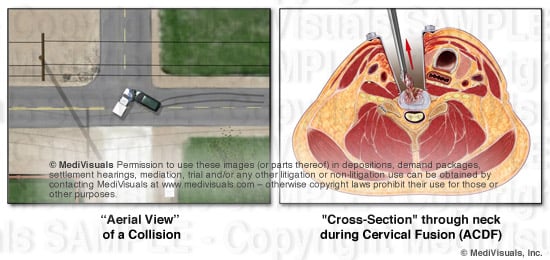

A way to perhaps explain how sectional views help decision makers appreciate relevant anatomical and pathological relationships is to compare them to aerial views or photographs of the scene of a collision. Space is defined in three planes. Only two of these planes can effectively be demonstrated in a two-dimensional rendering. For example, aerial views have long been used to help explain the positions of vehicles and structures that simply can't be appreciate from "street views". When viewing the scene of a collision from a "street view", one can appreciate vertical and horizontal distances, but not depth; distances close to and far from the viewer's perspective are very difficult to appreciate (see the below figures). By comparison, when viewing an operative site through a "surgeon's view", vertical and horizontal distances can be appreciated, but the depth of the incision and the relationships of the various structures within and around the incision are very difficult or impossible to appreciate.

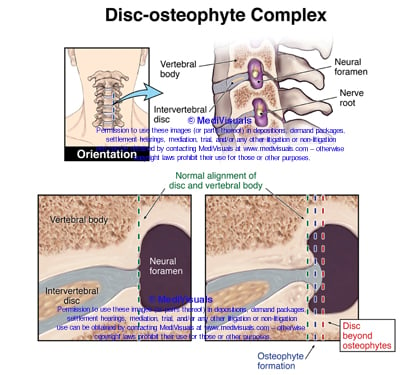

The "aerial view" of the collision scene allows the viewer to appreciate distances in two geographical planes as well (distances right and left, and toward and away from the "street view," but the ability to appreciate up and down is lost). Also, the locations of relevant structures or vehicles that may have been obstructed by nearby structures (such as buildings trees, signs, or other vehicles) can now be appreciated. Similarly, a sectional view of anatomy can help decision makers appreciate depth relationships of structures. Or, a sectional view of a step in a surgical illustration can allow the viewer to appreciate the depth of the surgery as well as the additional structures that may have been injured (or at risk of injury) during the invasive procedure. These specific depth relationships could not be appreciated from the "surgeon's view" of the same surgery shown in the above illustration.

Exhibits developed to help explain the invasive nature of a surgery and the disruption of the soft tissues during operative procedures are critical. For that reason, sectional views are critical in aiding a testifying physician to explain these issues. For example, the exhibit panel that demonstrates an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) that does not include a cross-section through the neck fails to emphasize the depth of the incision and disruption of tissues (essentially all the way to the center of the neck). This depth simply cannot be appreciated in a "surgeon's view".

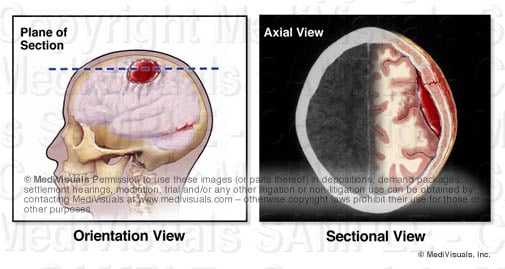

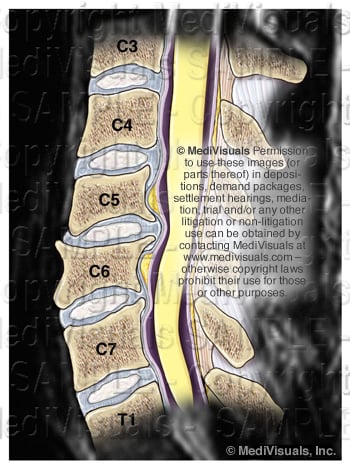

In order to appreciate cross-sections, orientation views that show the level and direction of the section are helpful (see below), or when time, budget, and presentation format (digital as opposed to a physical panel) allow, a short animation showing the sectional view actually coming out of the orientation view such as MediVisuals' "Scan SelectorTM" can be used.